READING TIME: 5 MINUTEN

STILL FROM FILM

than disappearance

STILL FROM FILM

PHOTO: HESTERLIENA WOLTHUIS

PROPOSITION

Veridianna Camilo Pattini – Faculteit Medische Wetenschappen

Some people see the rain as just another gray day, while others see it as the beginning of life.

“

‘Let me go, don’t clean me up anymore’

TEXT: KIRSTEN OTTEN / IMAGES: STILLS FROM THE FILM

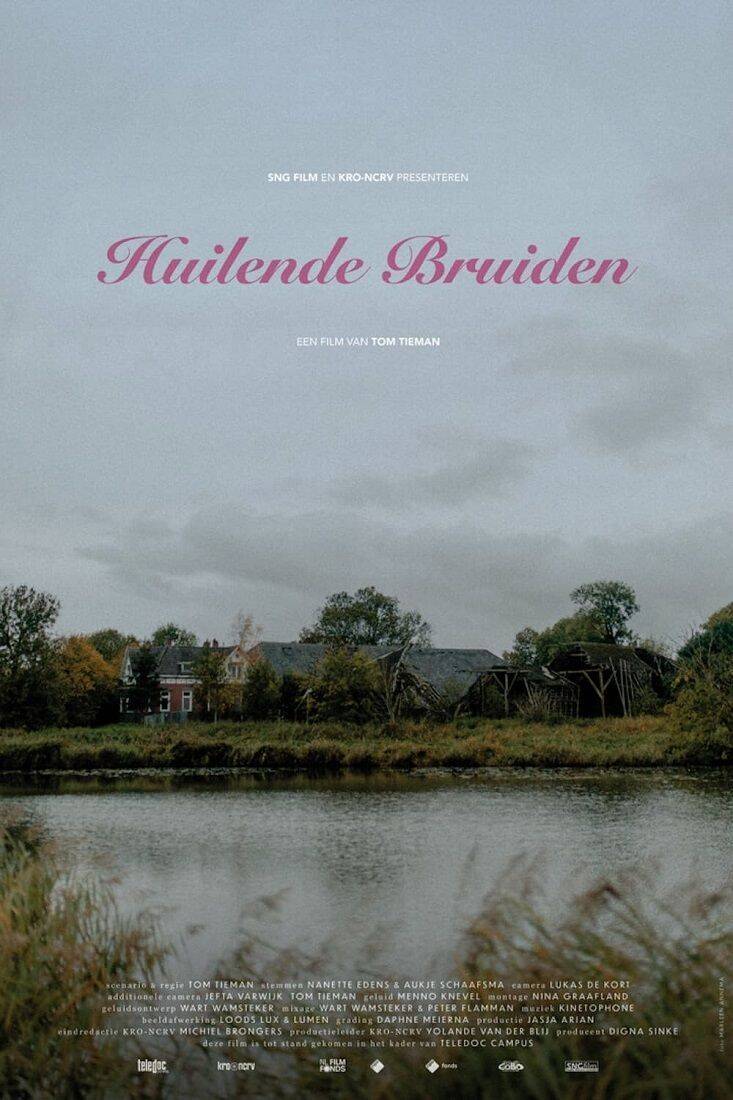

Filmmaker Tom Tieman regularly points his camera at the Groningen countryside.

In his documentary ‘Huilende bruiden’ (Crying brides), he uses two dilapidated farms to reflect on

the question: what should be preserved and what is the best way to do so?

After an HBO degree programme in Journalism – ‘too hyped, not my thing’ – Tom Tieman (1984) chose to pursue a degree in Arts, Culture and Media at the University of Groningen. He graduated with a thesis on German expressionist cinema in 2011. ‘This degree programme teaches you nothing and at the same time everything about filmmaking: watching attentively, analysing, but also planning and working independently. And I took classes from inspiring lecturers such as Susan Aasman, who introduced me to the documentaries of Digna Sinke, who became some kind of hero to me.’

Monumental manor farms

In the past years, Tieman created theatre shows, audio walks, and documentaries. In his works, decay and the countryside in Groningen are returning themes. ‘The book De Graanrepubliek (The Grain Republic) by Frank Westerman piqued my interest in the rich agricultural history of Oldambt, and the monumental manor farms that are typical for the area. They used to be a symbol of wealth, but these days, they are suffering from economic decline and the consequences of gas extraction.’

Peeling plaster

‘This is how, in 2021, the idea for the “Huilende bruiden” audio walk came to life. I wasn’t the one to coin this term, but I found it very fitting. The peeling plaster and weathered statues of women on the facades turn the formerly impressive farms into a sad sight.’ Tieman's film of the same name was released in 2024 and was awarded the Noorderkroon prize for best documentary at the Noordelijk Film Festival, just like his first documentary ‘De laatste boer van Euvelgunne’ (The last farmer of Euvelgunne, 2017).

Contrarian approach

What is worth preserving for the future and what is not? What is valuable? These are central questions in ‘Huilende bruiden’. ‘Ideally, I wanted Digna Sinke to produce this documentary. I decided to send her an email, and miraculously, she said yes! With her years of experience, as well as her contrarian approach, Digna guided me through the process. Whenever she heard that something was not possible, she would work for it even harder. I found her determination very inspiring.’

Heavily damaged

The film is a double portrait of two farms. One of them, a 159-year-old national monument, has been owned by the same family for generations. Because of land subsidence caused by gas extraction, the building has over one hundred large cracks. The roof is leaking and the doors no longer open. It is impossible to demolish the building because of its status as a national monument, but funding for renovations, which will cost a fortune, has not come through for years because the farm is located just outside the official earthquake area. In an act of protest and despair, the owners painted the facade bright pink.

The other farm, also heavily damaged and partly uninhabitable, is not a national monument, but the owner decided to accept the farm as it is. She decided to shut her eyes to the damages, almost literally, as she is losing her eyesight.

Poetic language

In the film, the farms themselves speak. While the viewer is shown the dimly lit buildings, past falsework and cracks, the farms use poetic language to reflect on their history and their fate: dilapidation. One of the farms says: ‘Let me go, don’t clean me up anymore. It’s not the collapsing that hurts, but the cleaning up. Cleaned up and forgotten.’ It is a vision underscored by Tieman.

Allowed to fall into ruin

‘There are about three hundred of these manor farms in East Groningen,’ Tieman says. ‘Many of them are already protected and in pristine condition. Earlier this year, it was announced that the national monument that was painted pink will also be renovated. That’s fantastic! But there are still farms that are less iconic that nobody wants to take care of anymore. I would like it if some of them weren't demolished but allowed to fall into ruin. They can become places where nature can take its course: bats and hares can hide there, and trees and plants can find their way.’

Spark our imagination

Tieman explains how this is already happening in England. ‘There are so many abandoned country houses, churches, you name it. People often choose not to demolish but simply to let these places be. Sometimes this happens in consultation with local residents who feel connected to their ruin.’ But unlike England, where ruins have been cherished for centuries, we prefer tidying up and repurposing. ‘Sometimes that’s a shame,’ Tieman thinks. ‘Ruins show us what once existed and spark our imagination. This is why they appeal to tourists, which may also be interesting for East Groningen. Which farms qualify for this? I am neither a historian nor a heritage keeper, so you shouldn’t ask me. The experts should figure that out.’

You can re-watch Tom Tieman's documentary ‘Huilende bruiden’ on NPO Doc here (in Dutch).

STILL FROM FILM

READING TIME: 5 MINUTES

STILL FROM FILM

Veridianna Camilo Pattini – Faculteit Medische Wetenschappen

Some people see the rain as just another gray day, while others see it as the beginning of life.

PROPOSITION

PHOTO: HESTERLIENA WOLTHUIS

“

‘Let me go, don’t clean me up anymore’

After an HBO degree programme in Journalism – ‘too hyped, not my thing’ – Tom Tieman (1984) chose to pursue a degree in Arts, Culture and Media at the University of Groningen. He graduated with a thesis on German expressionist cinema in 2011. ‘This degree programme teaches you nothing and at the same time everything about filmmaking: watching attentively, analysing, but also planning and working independently. And I took classes from inspiring lecturers such as Susan Aasman, who introduced me to the documentaries of Digna Sinke, who became some kind of hero to me.’

Monumental manor farms

In the past years, Tieman created theatre shows, audio walks, and documentaries. In his works, decay and the countryside in Groningen are returning themes. ‘The book De Graanrepubliek (The Grain Republic) by Frank Westerman piqued my interest in the rich agricultural history of Oldambt, and the monumental manor farms that are typical for the area. They used to be a symbol of wealth, but these days, they are suffering from economic decline and the consequences of gas extraction.’

Peeling plaster

‘This is how, in 2021, the idea for the “Huilende bruiden” audio walk came to life. I wasn’t the one to coin this term, but I found it very fitting. The peeling plaster and weathered statues of women on the facades turn the formerly impressive farms into a sad sight.’ Tieman's film of the same name was released in 2024 and was awarded the Noorderkroon prize for best documentary at the Noordelijk Film Festival, just like his first documentary ‘De laatste boer van Euvelgunne’ (The last farmer of Euvelgunne, 2017).

Contrarian approach

What is worth preserving for the future and what is not? What is valuable? These are central questions in ‘Huilende bruiden’. ‘Ideally, I wanted Digna Sinke to produce this documentary. I decided to send her an email, and miraculously, she said yes! With her years of experience, as well as her contrarian approach, Digna guided me through the process. Whenever she heard that something was not possible, she would work for it even harder. I found her determination very inspiring.’

Heavily damaged

The film is a double portrait of two farms. One of them, a 159-year-old national monument, has been owned by the same family for generations. Because of land subsidence caused by gas extraction, the building has over one hundred large cracks. The roof is leaking and the doors no longer open. It is impossible to demolish the building because of its status as a national monument, but funding for renovations, which will cost a fortune, has not come through for years because the farm is located just outside the official earthquake area. In an act of protest and despair, the owners painted the facade bright pink.

The other farm, also heavily damaged and partly uninhabitable, is not a national monument, but the owner decided to accept the farm as it is. She decided to shut her eyes to the damages, almost literally, as she is losing her eyesight.

Poetic language

In the film, the farms themselves speak. While the viewer is shown the dimly lit buildings, past falsework and cracks, the farms use poetic language to reflect on their history and their fate: dilapidation. One of the farms says: ‘Let me go, don’t clean me up anymore. It’s not the collapsing that hurts, but the cleaning up. Cleaned up and forgotten.’ It is a vision underscored by Tieman.

Allowed to fall into ruin

‘There are about three hundred of these manor farms in East Groningen,’ Tieman says. ‘Many of them are already protected and in pristine condition. Earlier this year, it was announced that the national monument that was painted pink will also be renovated. That’s fantastic! But there are still farms that are less iconic that nobody wants to take care of anymore. I would like it if some of them weren't demolished but allowed to fall into ruin. They can become places where nature can take its course: bats and hares can hide there, and trees and plants can find their way.’

Spark our imagination

Tieman explains how this is already happening in England. ‘There are so many abandoned country houses, churches, you name it. People often choose not to demolish but simply to let these places be. Sometimes this happens in consultation with local residents who feel connected to their ruin.’ But unlike England, where ruins have been cherished for centuries, we prefer tidying up and repurposing. ‘Sometimes that’s a shame,’ Tieman thinks. ‘Ruins show us what once existed and spark our imagination. This is why they appeal to tourists, which may also be interesting for East Groningen. Which farms qualify for this? I am neither a historian nor a heritage keeper, so you shouldn’t ask me. The experts should figure that out.’

You can re-watch Tom Tieman's documentary ‘Huilende bruiden’ on NPO Doc here (in Dutch).

Filmmaker Tom Tieman regularly points his camera at the Groningen countryside. In his documentary ‘Huilende bruiden’ (Crying brides), he uses two dilapidated farms to reflect on the question: what should be preserved and what is the best way

to do so?

TEXT: KIRSTEN OTTEN / IMAGES: STILLS FROM THE FILM